What's New in HCQM?

Case Management's Challenges and Opportunities

Teresa M. Treiger, RN-BC, MA, CCM, CHCQM, FABQAURP

Principal, Ascent Care Management

Case management means different things depending on who you ask. To those practicing professional case management, such as myself, it means being an advocate for the individual with whom I enter into an engagement. It means serving as a bridge, rather than as a crutch, to a person and his/her caregiver. It means adhering to practice standards and a code of conduct which guide my decision-making as well as my comportment. It means doing what I need to do, within my scope of practice, in order to help move my client and caregiver toward a better sense of health and ability to advocate for themselves.

In many care settings, case management has been reduced to a series of questions which drive the creation of a problem list that contains lots of boxes. While the checkboxes are great for data collection and reporting, they are anathema to many a case manager. Once all those boxes are checked off, the organization considers the “case” as closed. However, as a case manager, I never consider the individual who I serve as a “case” nor do I consider my work complete simply because all of those neat little boxes are checked off.

External factors impact my case management practice. Organizational policies, that drive many case management-related practices, are as unique as snowflakes. The continuous evolution of legislative and regulatory changes at federal and state levels, societal issues that rise in prominence, and service areas that expand as a result of the push to repatriate people from institutions to community-based care are significant areas where case management is relied upon to keep the healthcare ship afloat.

Selecting three (3) relevant issues regularly encountered by case managers proved a near impossible task. The wide variety of practice settings each have their own hot points of upheaval. Fire alarm topics change because of the nature of healthcare itself – ever-changing in its focus from one conflagration to the next. From a high-altitude perch, each case manager along the care continuum already has been or will soon be challenged by these three things - the opioid crisis, shared decision-making initiatives, and Long-Term Services and Supports.

The Opioid Crisis

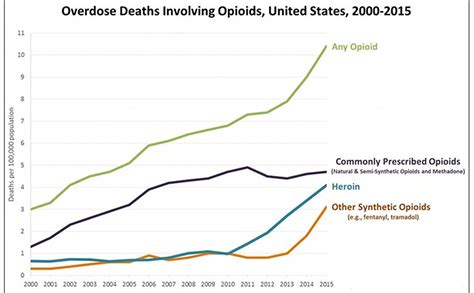

To anyone in healthcare who is not aware of the national disaster that is the opioid crisis, welcome back from the cave you’ve been living in. The opioid epidemic has reached alarming levels in all parts of the United States and affects the lives of thousands of individuals and families. More than three out of five drug overdose deaths involve an opioid.

1 The U.S. opioid epidemic contributes to drug overdose deaths that nearly tripled between 1999 and 2014.1 Among 47,055 drug overdose deaths that occurred in 2014 in the United States, 28,647 (60.9%) involved an opioid.

1 Illicit opioids are contributing to the increase in opioid overdose deaths.

2,3 The following graphic illustrates these facts.

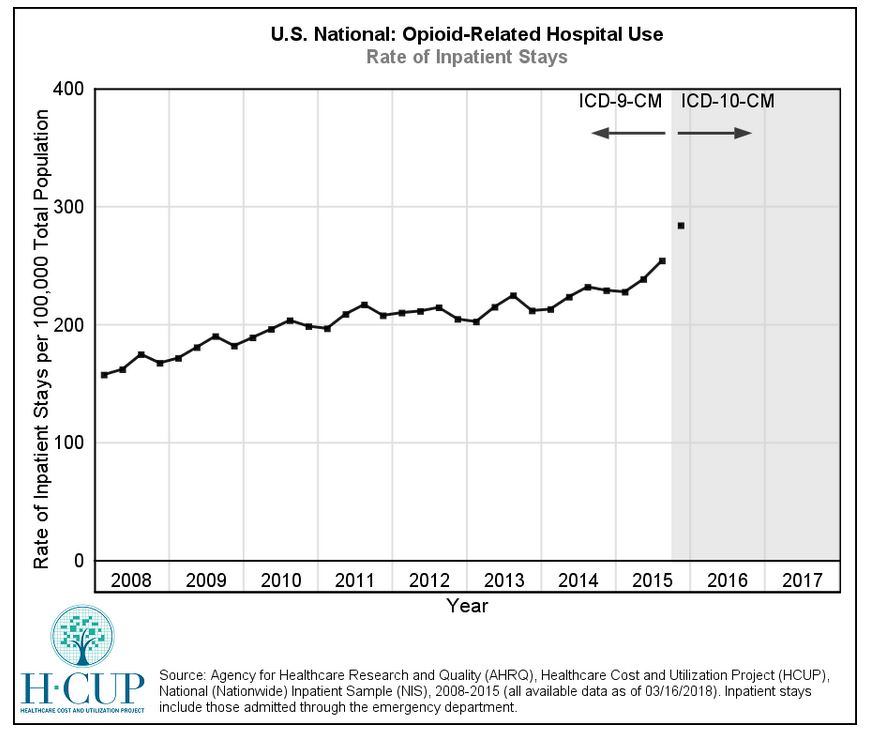

Case managers face opioid-related care coordination challenges regularly. Hospitalizations related to opioid misuse and dependence increased dramatically, with the rate of adult hospital inpatient stays per 100,000 population nearly doubling between 2000 and 2012.

4

Case managers in both acute care and managed care settings can attest to the challenges of this population. The opioid misuse variable affects hospital care and transition planning. A few of the issues relating to opioid-related admissions include longer lengths of stays, inter-personal relations, shame, family dynamics and support systems, and simply trying to find a post-acute facility with an open bed for a willing addict just to name a few.

But a more discrete and serious issue lurks just under the surface. It is our personal beliefs and prejudices about people suffering from substance misuse and addiction. Speaking for myself, every encounter I have with someone struggling with substance misuse and addiction is colored by the fact that I watched a family member struggle with heroin and crack addiction since his late teens. So many detox admissions, homelessness, Salvation Army, and as he walked away from my home into one of the worst blizzards in New England history. Once you have walked down this road with a loved one, you are never quite the same. You witnessed someone change from a loving, caring person into a zombie who will do anything to score their next hit. It becomes increasingly easy to objectify someone struggling with addiction because the person neither behaves nor looks like a non-addicted person. I had to stop thinking about my nephew as he used to be. Objectifying him into the “addict collective” was simply my attempt at self-preservation. I know I am not the only healthcare professional in this situation.

In my past experience as a managed care case manager, I was powerless to do anything aside from facilitate transition planning before sending a referral to the Behavioral Health Management team. Our plan carved-out those benefits and case management occurred at the other company. It leaves one to consider whether that is how managed care organizations should continue to address opioid-addicted members? What continues to take place in many detoxification and recovery programs is that people are herded through a revolving door of the same interventions that have not worked for them in the past. How does that translate into evidence-based care? Where is effective population health improvement and cost reduction in the current process? Our healthcare machine must begin to address opioid addiction as a long-term commitment to improve the health of those diagnosed with a disease that carries a life sentence. Consistent, collaborative, and integrated case management can be an essential ingredient of a population health approach to opioid addiction management.

Shared Decision-Making

Taking the time to assess each patient’s understanding about their health conditions and treatment options is a significant aspect of case management practice. The case management assessment is a discovery process which uncovers the bio-psycho-social-spiritual details of each client. The case manager delves into literacy issues as well as personal, cultural and linguistic preferences. This level of detail informs the case management plan of care which incorporates each patient’s ability to participate in healthcare decision-making. The subsequent phases of the case management process take these personalized details and aligns the patient’s preferences into the context of quality healthcare delivery and care coordination efforts.

5

The model of two-way communication, known as shared decision making (SDM), is critical to the improvement of person-centered care. Both healthcare professionals and patients should be able to comfortably discuss risks, benefits, and care challenges, choices and impacts, as well as costs of care.

5 However, the deck is stacked against most patients because they do not have years of education and experience in their respective hands.

Picture a conversation as a see-saw. Each person goes up and down at a fairly steady rate. Now consider a provider-patient dialogue. If healthcare knowledge and experience are the weight assigned to each participant, the see-saw would invariably be tipped in favor of the provider. This leaves the patient with his/her legs perpetually dangling in mid-air. That position is one from which few people can carry on a productive discussion.

SDM is a communication process where clinicians and patients collaborate to make healthcare decisions that align with what matters most to the person receiving care. There are three components of SDM:

6

- clear, accurate, and unbiased medical evidence about reasonable alternatives—including no intervention—and the risks and benefits of each;

- clinician expertise in communicating and tailoring that evidence for individual patient; and

- patient values, goals, informed preferences, and concerns, which may include impacts of treatment.

By definition, case managers leverage communication as a means of conducting effective practice, “Case Management is a collaborative process of assessment, planning, facilitation, care coordination, evaluation and advocacy for options and services to meet an individual’s and family’s comprehensive health needs through communication and available resources to promote patient safety, quality of care, and cost-effective outcomes”.

7 Communication is a key aspect of case management’s philosophy and guiding principles. The Case Management Society of America (CMSA) elaborates that “Successful care outcomes cannot be achieved without the specialized skills, knowledge, and competencies professional case managers apply throughout the case management process”, included in these skills motivational interviewing, positive relationship-building, and effective communication.

7

Clearly, the concept of SDM is embedded in professional case management practice as evidenced by a sampling of CMSA practice standard passages:

7

- “Facilitating communication and coordination among members of the interprofessional health care team and involving the client in the decision-making process” (excerpt from Professional Case Management Roles and Responsibilities).

- “The case management process is cyclical and recurrent, rather than linear and unidirectional. For example, key functions of the professional case manager, such as communication, facilitation, coordination, collaboration, and advocacy, occur throughout all the steps of the case management process and in constant contact with the client, client’s family or family caregiver, and other members of the interprofessional health care team” (excerpt from the Case Management Process).

- “The professional case manager should facilitate coordination, communication, and collaboration with the client, client’s family or family caregiver, involved members of the interprofessional health care team, and other stakeholders, in order to achieve target goals and maximize positive client care outcomes” (excerpt from the practice standard, Facilitation, Coordination, and Collaboration).

With the call to action issued by the National Quality PartnersTM (NQP) regarding SDM, there is an impending push to conduct all patient communications within SDM parameters as put forth in the Call to Action, “... for all individuals and organizations that provide, receive, pay for, and make policies for healthcare to embrace and integrate shared decision making into clinical practice as a standard of person-centered care”.

8

The six (6) fundamentals and associated key points identified by NQP are:

8

|

Fundamental Principle

|

Key Point(s)

|

|

Promote leadership and culture

|

- Implementing SDM requires support from leadership at all levels (e.g., board of directors, C-suite, division & department leaders)

- SDM should be framed within the context of patient rights and responsibilities

- Promote SDM as a means through which to promote person-centered care

|

|

Enhance patient education and engagement

|

- Provide SDM education for patient and caregivers

- Allow time to absorb SDM approach and reinforce education

- Provide relatable scenarios applying SDM

|

|

Provide healthcare team training

|

- Educate employees about SDM benefits

- Training should include role play and coaching, conducting difficult conversations, and allowing patient values to guide decision-making

|

|

Take concrete actions

|

- Healthcare organizations must engage in SDM as a central aspect of care decisions

- Identify standardized documentation that reflects SDM approach

|

|

Track, monitor, and report

|

- Identify appropriate mechanisms to track, monitor, and report clinician and care team SDM engagement

- Develop SDM data collection and regular sharing of performance, patient experience, and satisfaction data

- Document reasons why patient elected not to participate in SDM

|

|

Establish accountability

|

- Organizations must articulate clear expectations and establish incentives for engagement of SDM

- Incorporate SDM measures into performance management systems

|

The impact resulting from widespread adoption of this call to action will most certainly be felt by practicing case managers in the form of new policies and procedures as well as additional documentation responsibilities. However, if this call to action is undertaken and implemented, it will be tweaked to fit into each practice setting and/or healthcare-related organization. Practice standards and competency-based practice paradigms (e.g., COLLABORATE©) and frameworks (e.g., .e4™) must continue to emphasize communication skills competence. Certification examinations should also begin exploring the inclusion of questions associated with SDM practice because fluency with these practices should be considered as part of the essential foundation of practice.

Long-Term Services and Supports

Long-Term Services and Supports (LTSS) providers are a critical link to safe home and community transitions of care but are not routinely included in the healthcare team construct, especially as pertains to care transitions from inpatient facilities to “home”. LTSS encompass a variety of paid and unpaid medical and personal care assistance to individuals faced with progressive challenges to completing self-care tasks. The engagement of services may be for a period of weeks, months, or even years. The cause of self-care difficulties include age, chronic illness, and/or disability (e.g., physical, cognitive).

9 Most traditional health and indemnity plans do not include LTSS benefits.

Family caregivers often provide assistance with activities of daily living (e.g., bathing, dressing, eating) and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (e.g., shopping, financial management). Although these supports are critically important to the well-being of the person receiving care, the family caregiver role has evolved to the point that expected routine care tasks are much more complex to the point that they used to be activities that required an inpatient admission.

10 In 2012, the American Association of Retired People (AARP) Public Policy Institute and the United Hospital Fund (UHF) conducted the first nationally representative population-based online survey of family caregivers to determine what medical and/or nursing tasks they routinely performed.10 The findings of this survey challenged common perceptions of family caregiving.

According to the survey, almost half of family caregivers perform activities they referred to as medical or nursing tasks. Forty-six percent (777 of the 1,677) reported performing the following tasks frequently:

10

- Medication management, including injections and intravenous administration (78%)

- Assistive device (e.g., canes walkers) for mobility (43%)

- Preparing special diets (41%)

- Performing wound care, ostomy care, treatment of pressure sores, application of ointments, administration of prescription drugs and bandages for skin care (35%)

- Using meters or monitors (e.g., glucometers, oximetry, blood pressure, other test kits, telehealth equipment) (32%)

- Continence management (e.g., administering enemas, incontinence equipment and supplies) (25%)

- Operating durable medical equipment (e.g., lifts to get people out of bed, hospital beds, geri-chairs) (21%)

- Operating medical equipment (e.g., mechanical ventilators, tube feeding equipment, home dialysis, suctioning) (14%)

According to the survey, the majority of family caregivers are “women age 50 and over who care for a parent for at least one year while maintaining outside employment”.

10

Paid LTSS workers may be required to augment or replace the family caregiver.

9 In the United States, a majority of LTSS is provided by unpaid, unskilled workers. These workers are employees of the coordinating agency or hired directly by the patient. Because of the high level of effort for relatively low wages, there is quite a bit of churn in this workforce. Quite literally, in some states these workers, who are responsible to care for a human being’s essential needs and medical treatments, get paid more to flip hamburgers at their local fast-food restaurant.

Although service providers approach delivery differently, LTSS generally include support for the following:

9

- Assistance with activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living,

- Nursing facility care,

- Adult daycare programs,

- Home health aide services,

- Personal care services,

- Transportation,

- Supported employment, and

- Care planning and care coordination.

Quite literally, millions of people need LTSS. Those in need include:

9, 10

- Elderly and non-elderly,

- People with intellectual and developmental disabilities,

- People with physical disabilities, and

- People with behavioral health diagnoses (e.g., dementia, spinal cord, traumatic brain injuries, and/or disabling chronic conditions).

A beneficiary’s age, gender, socioeconomic status, living arrangement, and access to information about care options, in addition to his or her health and disability status, may influence the types and amounts of LTSS utilized and the duration of care.

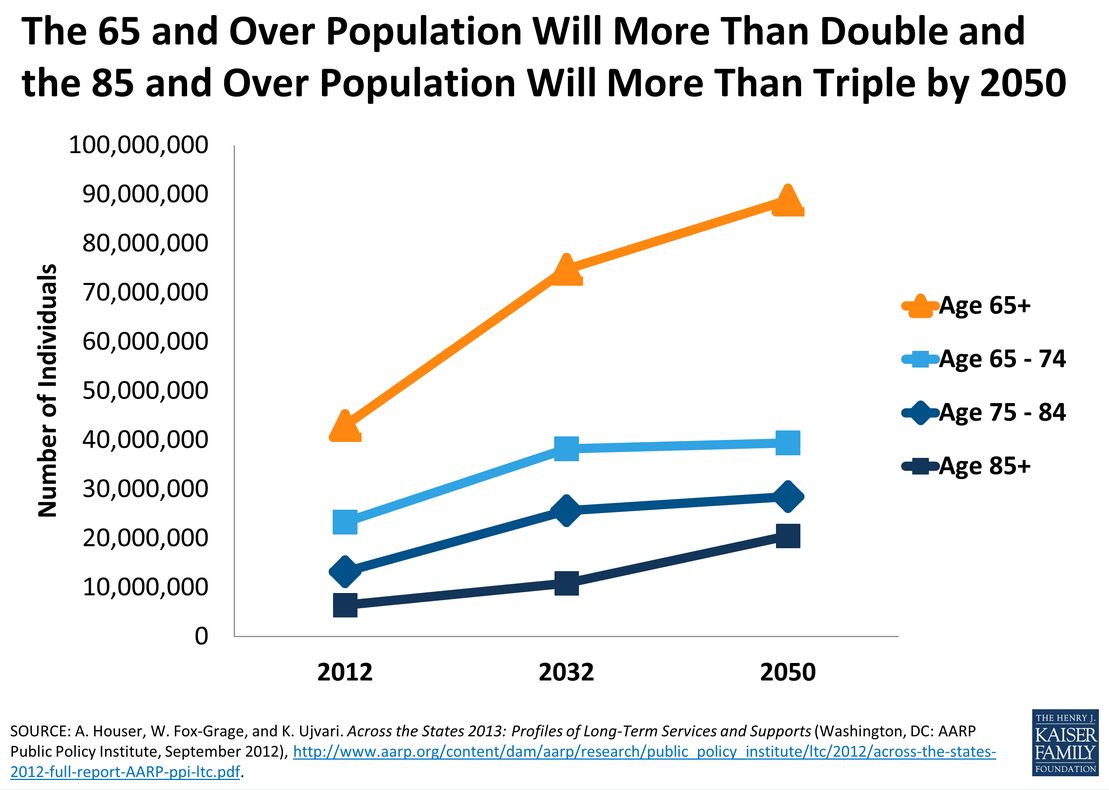

9, 10 The number of potential LTSS recipients is expected to increase as demonstrated in the following Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) graphic:

11

These numbers will challenge case managers in a variety of care settings because, as experts in care coordination, case management is the doorstep on which the responsibility to establish and maintain the bulk of these services will be placed. LTSS providers must be a consistent part of the patient’s healthcare team in order to appropriately transition patients between care settings.

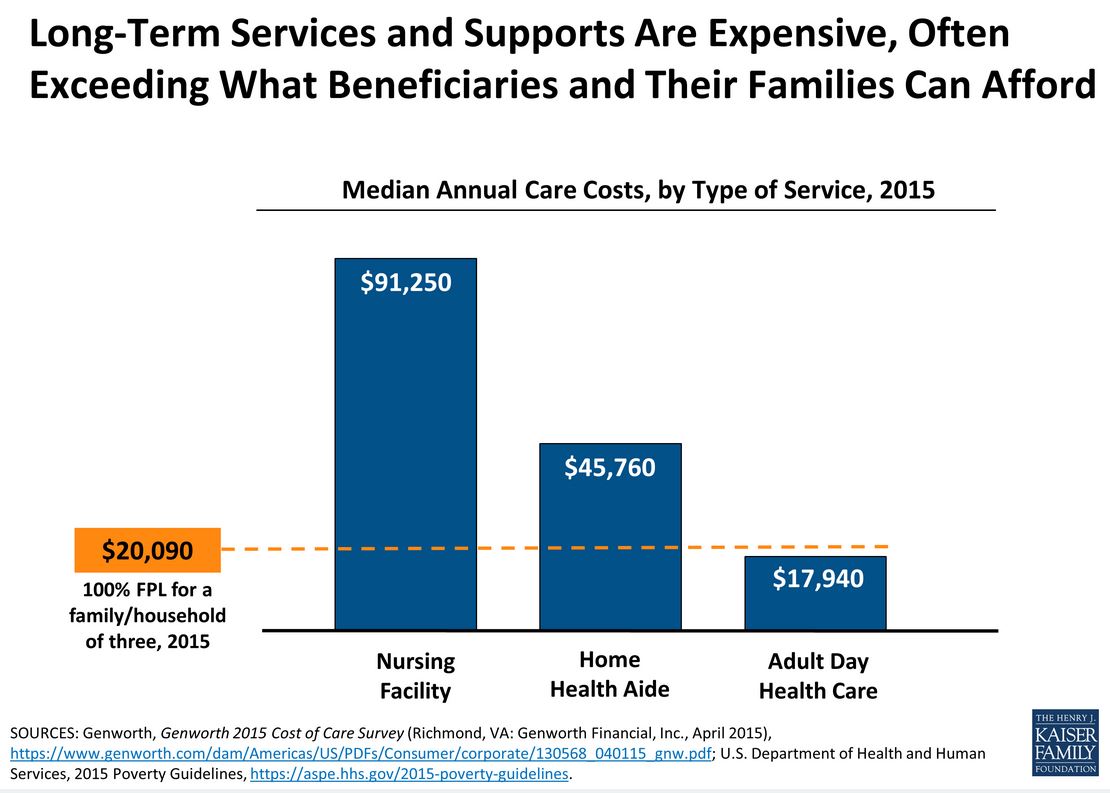

The payor source also figures into the complexity of care coordination. Medicaid pays a lion’s share of LTSS care costs. Almost half of the community-living seniors have an LTSS need.

11, 12 However, Medicare-insured seniors typically do not have LTSS coverage. LTSS costs frequently exceed what a patient can afford on top of other personal and household expenses. Although institutional care (e.g., nursing facilities, residential care facilities) are the highest cost, the price tag for a home health aide is substantial.

11, 12, 13 The following graphic demonstrates a cost comparison.

9

There are state-to-state variations in service scope and program regulation due, in part, to the fact that LTSS coverage is primarily Medicaid. State plans spell out the types of services that its LTSS program(s) covers. In addition, LTSS services may also be covered by waiver. Under a Medicaid waiver, a state can waive certain Medicaid program requirements. This allows the state to provide care for people who might not otherwise be eligible under Medicaid.

14 It also allows for the covered population to be strictly defined by the state.

There is a degree of federal control exerted over waiver programs because states must submit an application for approval for their program(s). States are allowed to develop programs to meet the needs of people who prefer to receive LTSS in their home or community, rather than in an institutional setting. Where LTSS is concerned, by 2009, nearly one million individuals across the U.S. were receiving services under HCBS waivers.

14

In addition to waiver programs, there are other programs which may be leveraged for care delivery. The Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE) is a type of home and community based service (HCBS) providing medical services and supports for everyday living needs of certain elderly individuals, most of whom are dual-eligible (eligible for Medicare and Medicaid). Services are provided by an interdisciplinary team of professionals (e.g., primary care physician, nurse, social worker, physical therapist, dietitian, pharmacist). Enrollment qualifications restrict who may enter the PACE program. There is also a stipulation that a PACE participant not be concurrently enrolled in any other Medicare Advantage, Medicare Prescription Drug, or Medicaid prepayment plan, or optional benefit (e.g., 1915c waiver, Medicare hospice benefit).

15

Another program is Money Follows the Person (MFP). MFP allows Medicaid beneficiaries currently residing in long-term nursing homes and other types of facilities with more choice about where they receive LTSS.

16 There are currently forty-three (43) states plus the District of Columbia participating in the demonstration. The MFP Rebalancing Demonstration Grant helps states rebalance their Medicaid long-term care systems. Over 75,151 people with chronic conditions and disabilities have transitioned from institutions back into the community through MFP programs as of December 2016.

17

Again, case management will be tasked with the bulk of these complex transitions between institutional and home care settings. When people enrolled in these programs are admitted to an acute care setting, it sets into motion the return transition. LTSS providers consistently complain that they are neither notified of the admission of a client, nor involved in the transition planning for the client be it back to their home setting or to another inpatient facility.

18

We must begin to consistently invite LTSS providers to the healthcare team’s table in order to appropriately transition patients between care settings and maintain continuity of HCBS. The mechanics of how these provider and service coordination agencies are incorporated on care teams cannot hinge on whether or not they are part of an integrated network or an Accountable Care Organization. Many LTSS providers are small community-based agencies that not been on the radar in terms of supported technology upgrades or even accreditation. States are increasingly requiring these agencies to become accredited.

The National Committee on Quality Assurance (NCQA) introduced LTSS Case Management accreditation and distinction programs in 2017.

19 As states continue to expand waiver programs and community-based care initiatives, more are requiring provider accreditation as a qualification to receive payment. Many of these small, standalone agencies were not accredited but are now faced with meeting comprehensive standards and significantly more intense quality monitoring measures. To support LTSS organizations that are new to accreditation, NCQA created an LTSS Best Practices Academy. This is a private, interactive forum for professionals to discuss strategies for coordinating quality LTSS programs and learn more about developing programs that conform with accreditation expectations. The academy encourages discussions and information exchange through an online forum, newsletters, live webinars, and other means. LTSS providers seeking accreditation or distinction are stepping up their attention to quality care for this population.

20

True cross-continuum healthcare requires dedicated and collaborative efforts between all care team members. As the care continuum adopts SDM, the effort to include LTSS providers at the care team table must be undertaken. Established LTSS providers are already delivering services in the patient’s home. As the front-line of care coordination, case managers need education about LTSS including what it is, who provides it, who the payor(s) is/are, what waiver programs are, how waivers work, and who the primary contacts are at various local agencies.

Summary

Case management means different things depending on who you ask. To those practicing professional case management, it means being an advocate for individuals in my care. It means doing what is needed, within one’s scope of practice, to help move individuals toward better health and improving their ability to coordinate care and advocate for themselves. As time marches on, case managers will be called upon to undertake new and evolving roles and responsibilities. Providing education and support in advance of these challenges is in the best interest of case managers and ultimately the patients who we serve.

Hear more from Teresa Treiger about Case Management's Opportunities and Challenges and what they mean to other healthcare providers. Join us for an educational and interactive discussion at ABQAURP’s 42nd Annual Health Care Quality and Patient Safety Conference in San Antonio, TX on April 25-26, 2019. We look forward to seeing you there! Conference details: HERE.

REFERENCES

1. Rudd RA, Aleshire N, Zibbell JE, Gladden RM. Increases in drug and opioid overdose deaths—United States, 2000–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;64:1378–82. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6450a3.htm. Published January 1, 2016. Accessed July 9, 2018.

2. Gladden RM, Martinez P, Seth P. Fentanyl law enforcement submissions and increases in synthetic opioid-involved overdose deaths—27 states, 2013–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65:837–43. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/wr/mm6533a2.htm. Published August 26, 2016. Accessed July 9, 2018.

3. Peterson AB, Gladden RM, Delcher C, et al. Increases in fentanyl-related overdose deaths—Florida and Ohio, 2013–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65:844–9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27560948 . Published August 26, 2016. Accessed July 9, 2018.

4. Owens PL, Barrett ML, Weiss AJ, Washington RE, Kronick R. Hospital Inpatient Utilization Related to Opioid Overuse Among Adults, 1993–2012. HCUP Statistical Brief #177. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb177-Hospitalizations-for-Opioid-Overuse.jsp. Published August 2014. Accessed July 9, 2018.

5. Heath S. Using Shared Decision-Making to Spark Quality Patient Care. Patient Engagement HIT. https://patientengagementhit.com/news/using-shared-decision-making-to-spark-quality-patient-care. Published August 18, 2017. Accessed July 9, 2018.

6. National Quality Forum. Shared Decision Making: A Standard of Care for All Patients. https://www.qualityforum.org/NQP/Shared_Decision_Making_Action_Brief.aspx. Published October 3, 2017. Accessed July 9, 2018.

7. Case Management Society of America. CMSA Standards of Practice for Case Management, revised. http://cmsa.org/sop. Published June 2016. Accessed July 9, 2018.

8. National Quality Forum. Shared Decision Making: A Standard of Care for All Patients. https://www.qualityforum.org/NQP/Shared_Decision_Making_Action_Brief.aspx. Published October 3, 2017. Accessed July 9, 2018.

9. Reaves EL and Musumeci MB. Medicaid and Long-Term Services and Supports: A Primer. Kaiser Family Foundation Web site.

https://www.kff.org/medicaid/report/medicaid-and-long-term-services-and-supports-a-primer/. Published: Dec 15, 2015. Accessed July 10, 2018.

10. Reinhard SC, Levine C, Samis S. Home alone: family caregivers providing complex chronic care AARP Public Policy Institute. http://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/research/public_policy_institute/health/home-alone-family-caregivers-providing-complex-chronic-care-rev-AARP-ppi-health.pdf. Published October 2012. Accessed July 10, 2018.

11. Kaiser Family Foundation. Long-term care in the U.S.: a timeline. KFF Web site. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/timeline/long-term-care-in-the-united-states-a-timeline/. Published August 15, 2015. Accessed July 10, 2018.

12. Genworth. Genworth 2015 Cost of Care Survey. Genworth Web site. https://www.genworth.com/dam/Americas/US/PDFs/Consumer/corporate/130568_040115_gnw.pdf. Published April 2015. Accessed July 10, 2018.

13. Garfield R, Young K, Musumeci MB, Reaves EL, Kasper J. Serving low-income seniors where they live: Medicaid’s role in providing community-based long-term services and supports. http://kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/serving-low-income-seniors-where-they-live-medicaids-role-in-providing-community-based-long-term-services-and-supports/. Published September 18, 2015. Accessed July 10, 2018.

14. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid. State Medicaid plans and waivers. CMS Web site. https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/American-Indian-Alaska-Native/AIAN/LTSS-TA-Center/info/state-medicaid-policies.html. Last update April 2018. Accessed July 10, 2018.

15. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid. Programs. Programs of all-inclusive care for the elderly (PACE). CMS Web site. https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/Downloads/pace111c04.pdf. Accessed July 10, 2018.

16. Irvin CV, Denny-Brown N, Morris E, Postman C. Pathways to independence: transitioning adults under age 65 from nursing homes to community living. https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/ltss/downloads/mfpfieldreport19.pdf. Accessed July 4, 2018.

17. Medicaid.gov. Money follows the person. CMS Web site. https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/ltss/money-follows-the-person/index.html. Accessed July 4, 2018.

18. National Committee for Quality Assurance LTSS Best Practices Academy. Private conversations and correspondence with Academy members. January 1, 2017 to June 30, 2018.

19. National Committee for Quality Assurance. Accreditation of Case Management for Long-Term Services and Supports. NCQA Web site. http://www.ncqa.org/programs/accreditation/accreditation-of-case-management-for-ltss. Accessed July 10, 2018.

20. National Committee for Quality Assurance. LTSS Best Practices Academy. NCQA Web site. http://www.ncqa.org/programs/accreditation/accreditation-of-case-management-for-ltss/ltss-best-practices-academy. Accessed July 10, 2018.